The Diaphragm

- Lætitia

- Feb 14

- 13 min read

Updated: Feb 14

The diaphragm is a remarkable, dome-shaped muscle that plays several crucial roles in the human body, primarily related to breathing but also impacting other physiological functions.

It is much more than a breathing muscle. It acts as a dynamic separator of body cavities, a pump supporting circulation and lymph flow, a pressure regulator aiding various bodily functions, and a contributor to core stability and vocalization. Its health and function are vital for overall well-being.

Here's a detailed overview of its roles:

Primary Muscle of Respiration

The diaphragm’s role as the primary muscle of respiration is fundamental to life, making it one of the most important muscles in the body.

When the diaphragm contracts, it flattens and moves downward, increasing the volume of the thoracic cavity (chest). This expansion reduces pressure inside the lungs relative to the outside air, allowing air to flow in. When the diaphragm relaxes, it moves back to its dome shape, decreasing thoracic volume and pushing air out of the lungs.

This rhythmic contraction and relaxation are essential for efficient breathing and oxygen supply.

What and where is it?

The diaphragm is a thin, dome-shaped sheet of skeletal muscle that stretches across the bottom of the rib cage.

It attaches to the lower ribs, sternum (breastbone), and lumbar vertebrae of the spine.

Its dome shape curves upward into the chest cavity when relaxed.

Inhalation : What happens when we Breathing In

When you inhale, the diaphragm contracts and moves downward, flattening out.

This downward movement increases the vertical dimension of the thoracic cavity, effectively enlarging the chest space.

At the same time, the ribs slightly lift and expand outward due to the action of other respiratory muscles (intercostal muscles).

The increase in thoracic volume causes the pressure inside the lungs (intrapulmonary pressure) to drop below atmospheric pressure.

Air flows into the lungs through the nose or mouth to equalize this pressure difference.

This process allows oxygen-rich air to fill the alveoli (tiny air sacs in the lungs) where gas exchange occurs.

Exhalation What happens when we're Breathing Out

Exhalation is usually a passive process during normal, relaxed breathing.

The diaphragm relaxes and moves back upward into its dome shape.

This reduces the volume of the thoracic cavity, increasing the pressure inside the lungs.

Air is pushed out of the lungs as the pressure inside becomes higher than atmospheric pressure.

During forceful exhalation (like blowing out candles or during exercise), other muscles (abdominal muscles and internal intercostals) assist by pushing the diaphragm further upward and compressing the chest cavity.

Coordination with Other Respiratory Muscles

While the diaphragm is the main driver of breathing, other muscles assist:

External intercostal muscles help lift the ribs during inhalation.

Accessory muscles (like neck and shoulder muscles) engage during heavy breathing or respiratory distress.

The diaphragm’s efficient contraction-relaxation cycle is essential for smooth, rhythmic breathing.

Nervous System Control

The diaphragm is controlled by the phrenic nerve, which originates in the neck (C3-C5 spinal nerves).

This nerve sends signals that trigger diaphragm contraction automatically and continuously, even during sleep.

Voluntary control (like holding your breath or speaking) is also possible because the diaphragm is a skeletal muscle.

Gas Exchange and Life

By driving airflow in and out of the lungs, the diaphragm enables the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Oxygen is essential for cellular metabolism, energy production, and overall organ function. Efficient diaphragm function ensures that the body maintains proper oxygen levels and removes metabolic waste gases.

🌞

The diaphragm acts like a pump, changing the size of the chest cavity to create pressure differences that move air in and out of the lungs. Its contraction enlarges the chest for inhalation, and its relaxation allows exhalation. This continuous cycle is vital for breathing, oxygen delivery, and sustaining life.

Separation Between Thoracic and Abdominal Cavities

The diaphragm’s role as a separator between the thoracic and abdominal cavities is fundamental to both anatomy and physiology.

It is separating the chest cavity, containing heart and lungs from the digestive organs. This separation helps maintain the distinct pressures and functions of these two major body compartments.

Anatomical Barrier

The diaphragm is a thin, dome-shaped muscular sheet that physically divides the body into two main compartments:

Thoracic cavity (chest): Contains vital organs such as the heart, lungs, esophagus, and major blood vessels.

Abdominal cavity: Houses digestive organs like the stomach, liver, intestines, kidneys, and spleen.

This separation is crucial because these cavities contain organs with very different functions and environments.

Structural Features

The diaphragm attaches to the lower ribs, sternum, and spine, forming a tight, muscular partition.

It is pierced by key structures such as the esophagus, aorta, and inferior vena cava, which pass through specialized openings called hiatuses.

Despite these openings, the diaphragm maintains a strong, flexible barrier that supports organ positioning and function.

This Separation is important for:

1. Maintaining Distinct Pressure Zones

The thoracic cavity operates under negative pressure during inhalation to draw air into the lungs.

The abdominal cavity generally maintains positive pressure, especially during activities like digestion, defecation, or childbirth.

The diaphragm’s barrier function allows these pressure differences to coexist without interference.

This pressure separation is essential for efficient lung inflation and deflation as well as proper function of abdominal organs, which rely on stable pressure for digestion and waste elimination.

2. Preventing Organ Displacement

The diaphragm keeps thoracic and abdominal organs in their respective spaces.

This prevents organs from shifting or compressing each other, which could impair function.

For example, it stops abdominal organs from pushing upward into the chest cavity during increased abdominal pressure (e.g., coughing, heavy lifting).

3. Facilitating Coordinated Organ Movement

While separating the two cavities, the diaphragm also allows coordinated movement:

During breathing, the diaphragm contracts and moves downward, gently compressing abdominal organs. This movement aids digestion by massaging the stomach and intestines, promoting peristalsis (the wave-like muscle contractions that move food).

The diaphragm’s flexibility supports this dynamic interaction without compromising the integrity of either cavity.

4. Supporting Protective Functions

The diaphragm’s muscular barrier helps protect the lungs and heart from abdominal trauma.

It also contributes to the pressure regulation that supports venous return and lymphatic flow, linking respiratory and circulatory health.

🌞

The diaphragm acts as a vital anatomical and functional boundary between the chest and abdominal cavities. By maintaining distinct pressure zones and organ separation, it ensures the smooth operation of respiratory and digestive systems. This separation supports the body’s complex choreography of breathing, circulation, digestion, and core stability—much like a well-designed partition in a greenhouse that protects and nurtures different plant environments side by side. |

Assisting Circulation and Venous Return

The diaphragm plays a subtle but powerful role in supporting blood circulation, particularly by aiding venous return—the flow of blood back to the heart.

The diaphragm’s movement during breathing helps create pressure changes that assist the return of venous blood to the heart, especially from the lower parts of the body. This "respiratory pump" effect supports cardiovascular function and efficient blood circulation.

The Respiratory Pump Mechanism

The diaphragm’s rhythmic contraction and relaxation during breathing create pressure changes within the thoracic and abdominal cavities.

When you inhale, the diaphragm contracts and moves downward, expanding the chest cavity and lowering pressure inside the thorax.

Simultaneously, this downward movement increases pressure in the abdominal cavity.

The pressure gradient between the abdomen (higher pressure) and thorax (lower pressure) encourages blood in the large veins of the abdomen and legs to flow upward toward the heart.

How Pressure Changes Help Venous Blood Flow

1. Promoting Venous Return from the Lower Body

Veins, especially in the legs and abdomen, rely on pressure differences and muscle contractions to push blood back to the heart.

Unlike arteries, veins have thin walls and valves but lack strong muscular walls to propel blood.

The diaphragm’s movement acts like a pump:

Increased abdominal pressure during inhalation squeezes veins in the abdomen.

Decreased thoracic pressure creates a suction effect in the chest veins.

This coordinated action helps overcome gravity and resistance, efficiently returning blood to the heart.

2. Supporting Right Heart Function

The increased venous return fills the right atrium and ventricle of the heart more effectively.

This optimizes cardiac output—the amount of blood the heart pumps per minute—supporting oxygen delivery to tissues.

Efficient venous return also helps maintain stable blood pressure and prevents blood pooling in the lower limbs.

Additional Circulatory Benefits

Enhancing Lymphatic Flow

The diaphragm’s pressure changes also stimulate lymphatic vessels, which rely on external forces to move lymph fluid. Improved lymphatic drainage supports immune function and reduces fluid buildup (edema).

Reducing Venous Stasis and Risk of Clots

By promoting continuous blood flow, the diaphragm helps prevent venous stasis—a condition where blood pools and clots can form, especially in the legs (deep vein thrombosis). This is particularly important during prolonged sitting or immobility.

In conditions where diaphragm movement is impaired (e.g., paralysis, chronic respiratory diseases), venous return may be compromised. This can contribute to swelling, fatigue, and cardiovascular strain.

Techniques like deep breathing exercises and inspiratory muscle training can help restore diaphragm function and support circulation.

🌞

The diaphragm mechanism is essential for maintaining efficient circulation, supporting heart function, and preventing blood pooling.

Like the tides moving in harmony with the moon, the diaphragm’s movement orchestrates a vital flow that sustains the body’s life currents.

Role in Intra-abdominal Pressure Regulation

The diaphragm’s role in intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) regulation is a vital, often overlooked function that connects breathing with core stability and essential bodily processes.

By contracting, the diaphragm increases intra-abdominal pressure, which is important for Stabilizing the core during heavy lifting or straining as well as assisting bodily functions like defecation, urination, and childbirth by providing pressure support.

What is Intra-abdominal Pressure?

Intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) refers to the pressure within the abdominal cavity, created by the contents of the abdomen (organs, fluids, and muscles).

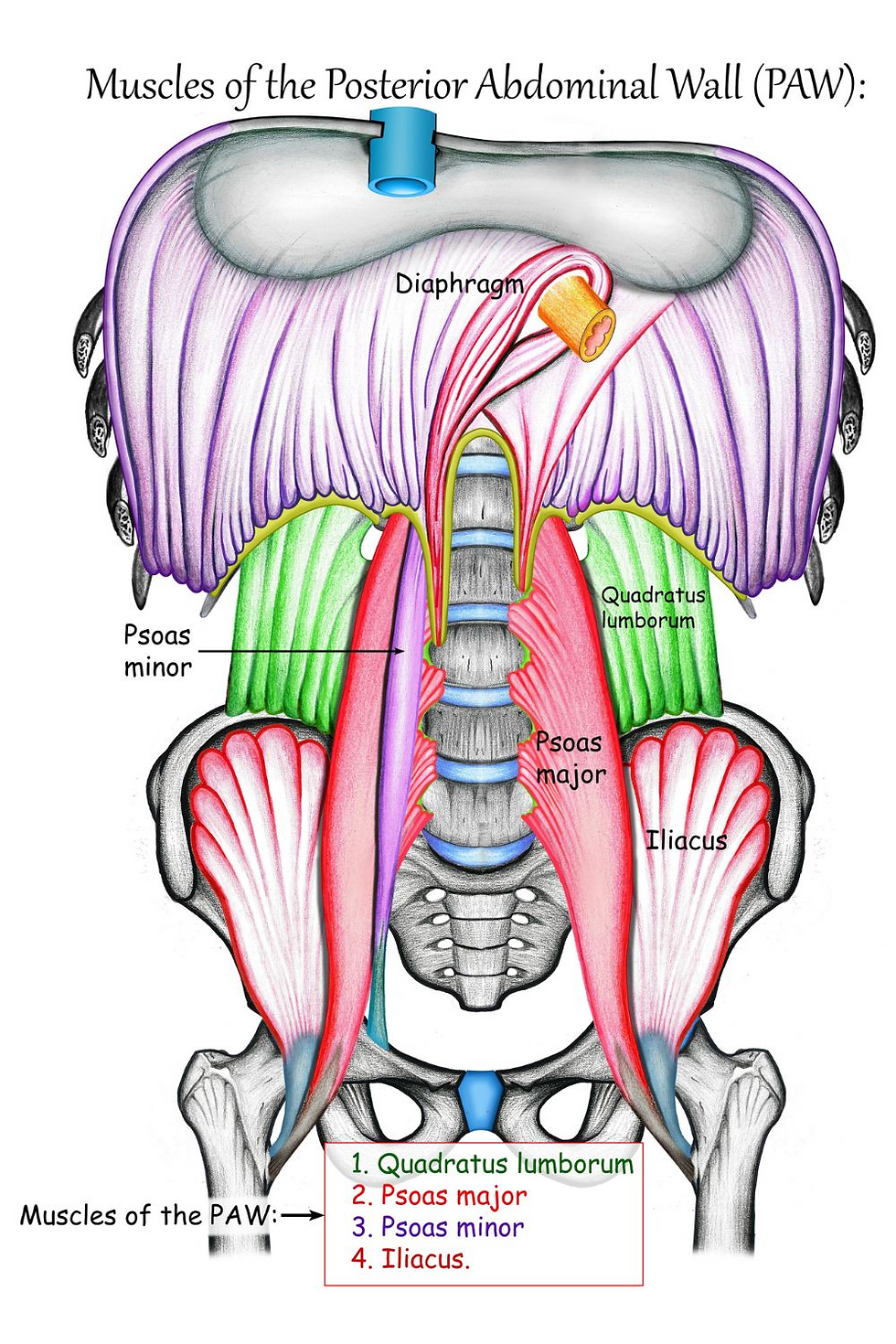

The diaphragm, along with abdominal muscles, pelvic floor muscles, and the lower back muscles, forms a dynamic "pressure chamber" that regulates IAP.

Proper regulation of IAP is crucial for maintaining spinal stability, organ function, and supporting bodily expulsive actions.

How the Diaphragm Regulates IAP

1. Diaphragm Contraction and Pressure Increase

When the diaphragm contracts (especially during deep inhalation or exertion), it moves downward.

This downward movement compresses abdominal contents, raising the pressure inside the abdominal cavity. The abdominal muscles and pelvic floor contract in coordination, creating a balanced increase in IAP.

Importance of Increased Intra-abdominal Pressure

Stabilizing the Core During Heavy Lifting or Straining

The rise in IAP acts like an internal brace or natural weight belt around the spine.

This pressure stabilizes the lumbar spine and pelvis, reducing strain on vertebrae and spinal discs.

It protects the back during activities like lifting heavy objects, pushing, pulling, or intense physical exertion.

Without this pressure support, the risk of injury, such as herniated discs or muscle strains, increases.

Assisting Bodily Functions Requiring Pressure Support

Defecation: Increased IAP helps push stool through the rectum during bowel movements.

Urination: Pressure supports the bladder and helps expel urine efficiently.

Childbirth: During labor, coordinated diaphragm and abdominal contractions increase IAP, aiding in the delivery of the baby.

These functions rely on a well-coordinated pressure system involving the diaphragm, abdominal muscles, and pelvic floor.

Coordination with Other Muscles

The diaphragm works synergistically with:

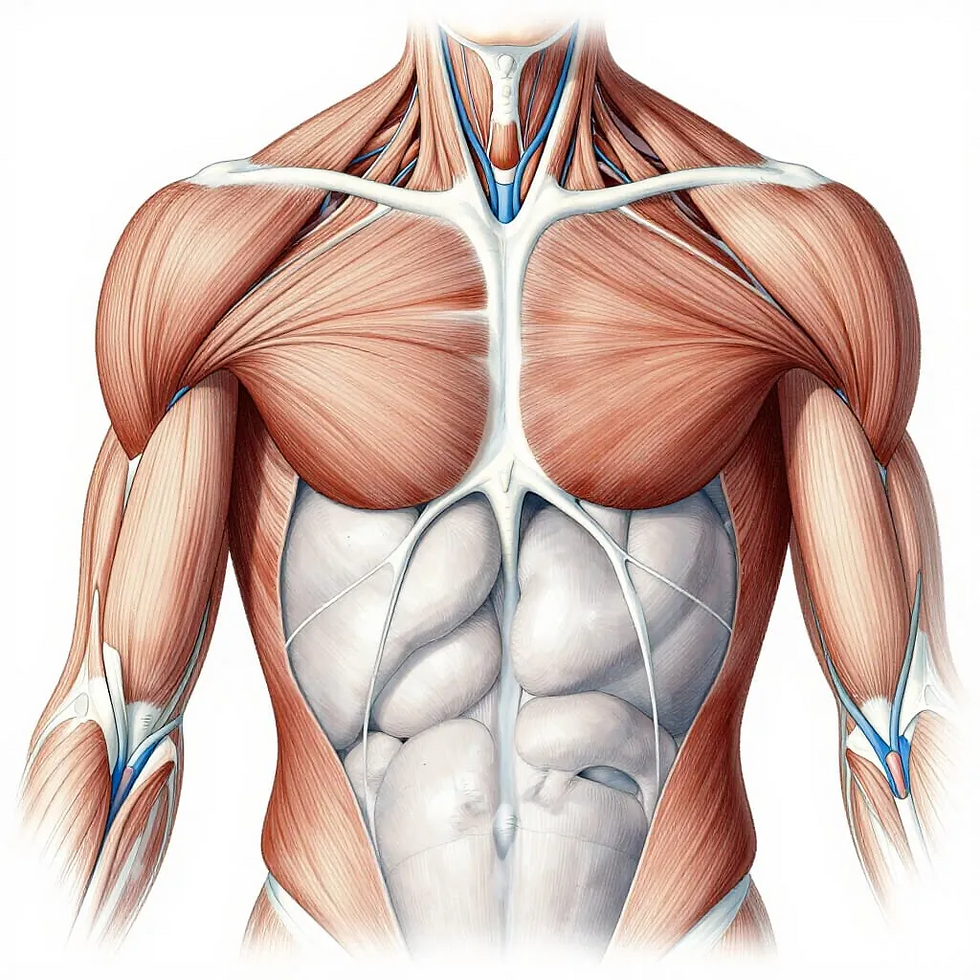

Abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis, obliques, transverse abdominis) that tighten the abdominal wall.

Pelvic floor muscles that act as a supportive base.

Back muscles that stabilize the spine.

This coordinated activity ensures that pressure is evenly distributed and controlled, preventing excessive strain on any one area.

Dysfunction or weakness of the diaphragm can lead to poor IAP regulation.

This may result in:

Core instability and increased risk of back pain or injury.

Problems with bowel or bladder control.

Difficulties during childbirth.

Conditions like chronic coughing, obesity, or pregnancy can challenge diaphragm function and IAP balance, sometimes leading to issues like hernias or pelvic floor disorders.

🌞

The diaphragm acts as a powerful piston that increases intra-abdominal pressure, creating an internal support system for the spine and vital bodily functions. By working in harmony with core and pelvic muscles, it stabilizes the body during heavy lifting and plays a critical role in expulsive functions like defecation, urination, and childbirth. This pressure regulation is like a natural, finely tuned air pump that protects and empowers the body from within.

Facilitating Lymphatic Flow

The diaphragm plays a subtle yet essential role in facilitating lymphatic flow, which is crucial for maintaining immune health and fluid balance throughout the body.

The pressure changes caused by diaphragm movement help promote lymphatic drainage, which is vital for immune function and fluid balance.

What Is the Lymphatic System?

The lymphatic system is a network of vessels, nodes, and organs that transports lymph—a clear fluid containing immune cells, waste products, and excess interstitial fluid.

It plays key roles in:

Immune defence by filtering pathogens and presenting them to immune cells.

Fluid balance by returning excess tissue fluid to the bloodstream.

Fat absorption from the digestive system.

How Diaphragm Movement Supports Lymphatic Drainage

Pressure Changes Drive Lymph Flow

The lymphatic system lacks a central pump like the heart.

Instead, lymph flow depends on external forces such as:

Skeletal muscle contractions.

Arterial pulsations.

Pressure changes from breathing, primarily driven by the diaphragm.

When the diaphragm contracts and descends during inhalation, it lowers pressure in the thoracic cavity and increases pressure in the abdominal cavity.

This pressure gradient acts like a pump, pushing lymph from the abdominal lymphatic vessels upward toward the thoracic duct and eventually back into the bloodstream.

Enhancing Thoracic Duct Function

The thoracic duct is the largest lymphatic vessel and empties lymph into the venous system near the heart.

Diaphragm movement creates a suction effect in the chest cavity, facilitating lymph flow through the thoracic duct. This ensures efficient drainage of lymph from the lower body and abdomen.

Importance of Efficient Lymphatic Flow

Immune Function

Proper lymph flow transports immune cells to sites of infection or injury.

It also removes cellular waste and pathogens, preventing accumulation and inflammation.

A well-functioning lymphatic system supports a robust immune response.

Fluid Balance and Edema Prevention

By returning excess interstitial fluid to circulation, the lymphatic system prevents fluid buildup (edema) in tissues.

Diaphragm-driven lymph flow helps reduce swelling, especially in the legs and abdomen.

Detoxification Support

Lymphatic drainage assists in clearing metabolic waste and toxins from tissues.

This cleansing process is vital for overall health and recovery.

Clinical and Lifestyle Relevance

Shallow or restricted breathing can reduce diaphragm movement, impairing lymphatic flow.

Conditions like lymphedema (lymph fluid buildup) or chronic inflammation may benefit from therapies that enhance diaphragm function.

Practices like deep breathing exercises, yoga, and gentle movement stimulate diaphragm activity and support lymphatic health.

🌞

The diaphragm acts as a vital pump for the lymphatic system, using pressure changes during breathing to propel lymph fluid through vessels and nodes. This facilitates immune surveillance, maintains fluid balance, and supports detoxification. Like the gentle tides moving nutrients and cleansing waters along a shoreline, diaphragm-driven lymphatic flow nurtures and protects the body’s internal environment.

Involvement in Vocalization and Speech

The diaphragm’s involvement in vocalization and speech is a fascinating example of how breathing mechanics intersect with communication. It helps control airflow through the vocal cords, contributing to voice modulation, speech, and singing.

How the Diaphragm Controls Airflow for Voice Production

Voice production depends on airflow passing through the vocal cords (also called vocal folds) located in the larynx (voice box).

The diaphragm, as the primary muscle of respiration, regulates the pressure and volume of air expelled from the lungs.

By controlling this airflow, the diaphragm influences the strength, pitch, and quality of the sound produced.

Speech

During normal speech, the diaphragm contracts to provide a steady, controlled stream of air.

This steady airflow allows the vocal cords to vibrate consistently, producing clear and intelligible sounds.

Variations in diaphragm contraction intensity adjust breath pressure, enabling changes in loudness and emphasis. Efficient diaphragm use prevents vocal strain by avoiding excessive force from throat muscles.

Singing

Singing requires precise control of breath and airflow to sustain notes, change pitch, and modulate volume.

The diaphragm supports this by:

Providing steady subglottic pressure (air pressure below the vocal cords) to maintain vocal cord vibration.

Allowing controlled breath release, which helps singers hold long notes and execute dynamic changes.

Coordinating with abdominal and chest muscles to adjust breath support for different vocal styles and ranges.

Singers often train diaphragmatic breathing to optimize vocal power, tone, and endurance.

Voice Modulation and Expression

Variations in diaphragm control influence how the voice rises and falls, enabling emotional expression and nuanced communication. Breath control affects pausing, phrasing, and rhythm in speech and singing, contributing to natural, engaging delivery.

Coordination with Other Muscles

The diaphragm works in concert with:

Intercostal muscles (between ribs) to adjust chest volume.

Abdominal muscles to regulate breath pressure and support.

Laryngeal muscles that adjust vocal cord tension.

This complex coordination allows fine-tuned control over airflow and vocal output.

Poor diaphragm function or shallow breathing can lead to: - Weak, breathy, or strained voice. - Vocal fatigue and hoarseness.

Speech therapists and vocal coaches emphasize diaphragmatic breathing to improve voice quality and prevent injury.

Techniques that strengthen diaphragm control benefit public speakers, singers, actors, and anyone relying on vocal performance.

🌞

The diaphragm is the engine behind the breath that fuels your voice. By controlling airflow through the vocal cords, it shapes the power, pitch, and expression of speech and singing. Like a skilled wind instrument player managing breath to create beautiful music, your diaphragm orchestrates the breath that brings your voice to life.

Supporting Posture and Core Stability

The diaphragm’s role in supporting posture and core stability is fundamental to how our bodies maintain balance, movement efficiency, and protect the spine. Through its connection with other core muscles (abdominals, pelvic floor, back muscles), the diaphragm helps maintain posture and spinal stability.

The Diaphragm as Part of the Core Muscle Group

The diaphragm is a central component of the core musculature, which also includes:

Abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis, transverse abdominis, internal and external obliques)

Pelvic floor muscles

Multifidus and erector spinae muscles of the back

These muscles form a cylindrical support system around the trunk, often described as a “core canister” or “corset.”

How the Diaphragm Supports Posture

Creating Intra-abdominal Pressure for Spinal Stability

When the diaphragm contracts during breathing, it moves downward and increases intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). This internal pressure acts like an inflatable cushion inside the abdomen, stabilizing the spine from the inside.

The pelvic floor and abdominal muscles contract simultaneously to contain and balance this pressure. This pressure system reduces the load on spinal vertebrae and discs, protecting them during standing, sitting, or movement.

Coordinated Muscle Activation for Postural Control

The diaphragm works in harmony with abdominal and back muscles to maintain an upright posture. For example, during standing or lifting, the diaphragm’s contraction helps brace the core, preventing excessive spinal flexion or extension.

This coordination supports the natural curves of the spine and helps maintain balance and alignment.

Diaphragm and Postural Alignment

Proper diaphragm function encourages an open chest and lifted ribcage, which promotes:

Neutral spine alignment.

Reduced forward head posture and rounded shoulders.

Conversely, poor diaphragm use (e.g., shallow chest breathing) can contribute to slouched posture, increasing strain on the neck and back muscles.

Impact on Movement and Injury Prevention

A stable core allows for efficient force transfer between the upper and lower body during activities like walking, running, or lifting.

By stabilizing the spine, the diaphragm helps prevent injuries related to poor posture, such as:

Lower back pain.

Disc herniation.

Muscle strains.

Core stability also improves balance and reduces fall risk, especially important as we age.

Weak or dysfunctional diaphragm activity is often linked to:

Poor posture.

Chronic back pain.

Reduced athletic performance.

Physical therapists and trainers emphasize diaphragm training as part of comprehensive core strengthening programs.

🌞

The diaphragm is much more than a breathing muscle—it is a key pillar of core stability and postural support.

By working in concert with abdominal, pelvic floor, and back muscles, it creates internal pressure and muscle coordination that stabilize the spine, maintain upright posture, and protect against injury. Like the foundation of a sturdy building, the diaphragm’s steady support underpins the body’s structure and movement.

Gently strengthen your Diaphragm

Diaphragm dysfunction reduces breathing efficiency, causing fatigue and shortness of breath. Strengthening it through diaphragmatic breathing, controlled exercises, posture improvement, and inspiratory muscle training can restore function and improve respiratory health. Consistent practice nurtures this vital muscle, much like tending to the roots of a tree to support its growth and resilience.

Good posture creates the ideal environment for your diaphragm to move freely, while core exercises stabilize your trunk, enhancing breathing efficiency and circulatory support. Together with breathing exercises, these habits build a resilient, well-functioning respiratory and circulatory system—like a strong tree trunk supporting healthy, expansive branches.

Combining deep, mindful breathing with gentle, rhythmic movements creates a powerful synergy that enhances diaphragm-driven pressure changes and stimulates lymphatic flow. These practices nurture your immune system, reduce fluid buildup, and promote overall vitality—much like a flowing river cleansing and nourishing the landscape.

Comments